By David Jackson, Leadership and local systems

Last Wednesday evening Innovation Unit, in partnership with A New Direction, hosted a ‘sold out’ (invitation only) screening of the documentary film “Most Likely to Succeed”. You can watch a trailer here: https://vimeo.com/122502930.

It is worth sharing some of the concept and content of the film.

Over 120 years ago, education underwent a dramatic transformation as the iconic one-room schoolhouse evolved into an effective universal system that produced an unmatched workforce tailored for the demands of the 20th Century. Astonishingly, despite seismic changes to society, including changes to employment patterns, the world economy, and information systems, education remains substantially the same – classrooms, lessons, subjects, age-cohorts, age-related tests, etc etc. As traditional white-collar jobs begin to disappear, the film suggests that this same system is potentially producing chronic levels of unemployment among graduates in the 21st Century. It has failed to tackle the 21st Century equity challenge and it has failed to adapt to the dramatically transformed life and work needs of today’s young people.

The film follows students into the classrooms of High Tech High, an innovative all-age group of 13 schools in San Diego which has evolved a dramatically different model of schooling and learning. There, over the course of a school year, two groups of ninth graders are followed taking on ambitious, project-based learning challenges that develop a range of personal and applied skills as well as offering access to deep content knowledge. “Most Likely to Succeed” points to a transformation in learning that may hold a key to success for millions of young people – and our nation – as we grapple with the ramifications of rapid advances in technology, automation and growing levels of economic inequality. More profoundly, it powerfully reveals the transformative potential of this project-based approach to the lives and self-image of the students and to the professional efficacy of the staff.

After the viewing, the 150 people who attended were invited to engage in informal conversation in the Barbican Cinema’s reception area. And here’s the thing. No-one wanted to depart. There was a level of animation and involvement and energy and passion for action that was utterly unique (in my experience). It wasn’t that everyone agreed with all aspects of the film. They didn’t. In fact, some of the film’s propositions are extremely challenging – depth not breadth; none-interventionist teaching; projects that endure for months; interdisciplinary rather than subject-based approaches; teachers free to teach whatever they wish, inspired by their passions….and many more. However, the drift of the film, its central proposition, its compelling message, seemed to be universally accepted.

That compelling message is that the model of schooling needs to change, and change dramatically, if we are to serve young people well for the future and if we are to tackle the equity and achievement gap (which, despite more than 100 years of trying, the current model has patently failed to do).

This second theme matters – and it matters even more than is exposed in ‘MLTS’. School remains the only entity in our modern world that has institutionalised the notion of ‘ability’. We talk about ‘able’ and ‘less able’ children in a way that would be utterly unacceptable in the adult world. We even group learning by spurious notions of ‘ability’ – notions which are, in effect, little more than socio-economic pre-determinants. But ones which then go on to become determinants.

High Tech High only has one grade – grade A. They expect every learner to achieve an A, and it is the responsibility of every other student to support them to get it. Their ‘classrooms’ are interdependent communities of learners. If this sounds glib, the principle success indicator they set themselves 12 years ago when the first school opened (with the same fully comprehensive intake they still have) is that every student – that is 100% of student, regardless of background or prior achievement history – should be able to progress to college and university. A dozen years later 98% of their students fulfil this – and 85% of their free school meals students complete degrees.

By any standard these are astonishing results – and they don’t even begin to represent the breadth and depth of achievement of students at High Tech High. But they will give some insight into why there was such energy at the Barbican event. People agreed with the proposition: our models of schooling and learning need to change, and they were awed by the evidence of what has already been achieved at High Tech High.

This, then, is both the scale of the challenge and the essence of a solution. School has to change and we have evidence that this is possible – possible, even, beyond our imaginings. We are locked into a time warp, with a mental model of ‘school’ that is debilitating, but we can also do something about it. We can redesign ‘school’. And the ‘we’ starts with the people in the room minded to do so, and then the people that they gather on the way.

As Margaret Mead so tellingly said: Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world; indeed, it is the only thing that ever has.

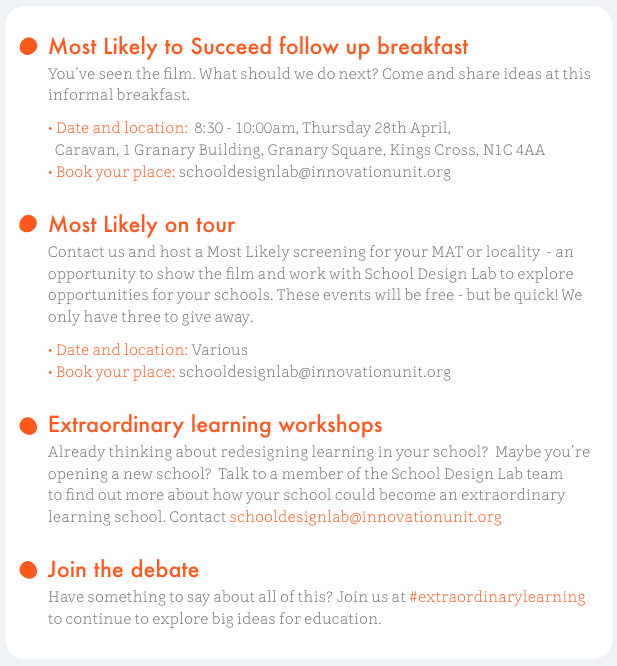

So, Innovation Unit will be following up. And this is how. If you are up for it – conversation, hosting a screening, workshops or debate – then all you have to do is join with some other thoughtful and committed citizens, and we can change the school experience for our young people.